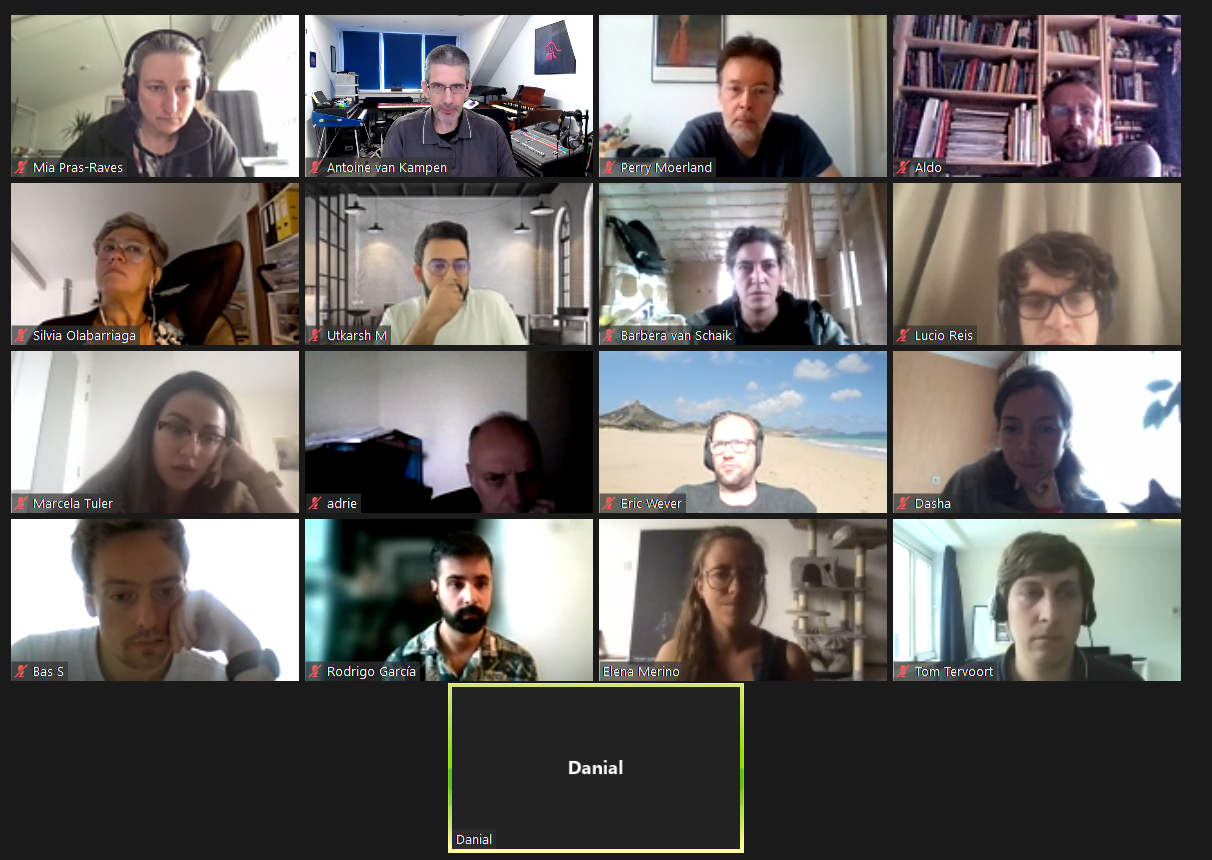

First BioMeC section day

Bioinformatics and biomedical computing is one of the sections of the department of Epidemiology and Data Science. This section comprises the research groups of Silvia Olabarriaga (e-Science) and Antoine van Kampen (Medical Bioinformatics).

On 15 September 2021 we organized our first BioMeC section day. More details will follow later.

Program

Part I. Interactive updates

- 9:20 Welcome (Antoine van Kampen / Silvia Olabarriaga)

- 9:30 – 9:45 Research Integrity (Antoine van Kampen).

- Plagiarism, authorship, reproducibility and beyond.

- 9:45 – 10:00 Data management (Silvia Olabarriaga).

- 10:00 – 10:15 Internship projects (Perry Moerland)

- Defining projects, guiding students, grading students

- 10:30 – 10:45 How to teach for BSc/MSc/PhD students. (Aldo Jongejan).

10:45 – 11:00 Coffee Break

Part II. Presentation Challenge

11:00-12:30 How to deliver your message (all PhD students)

Assignment

- Each presenter prepares a presentation about a specific part of his/her research

- Presentation max 10 minutes + 5 minutes discussion; no limit on the number of slides;

- Presentation should be sent to a.h.vankampen@amsterdamumc.nl one day prior to the meeting!!

- The content should (at least) include:

- Background

- Research Question

- Method/Approach

- Result (at least 1 fig and 1 table)

- Conclusion

- To support the content, also take good care of the design:

- Not too much text

- Consistent use of fonts, layout, colors, etc

- Clear and readable figures and tables

- …..

- Have a look at ‘How to give a dynamic scientific presentation’ (below)

- The opponent is expected to pay particular attention to the to content of the presentation. He/she is expected to

- ensure that the presenter keeps time;

- ask one critical question about the presented research during the discussion;

- guide the discussion after the presentatioN

12:30-13:30 Lunch + assignment

Part III. Surprise session

13:30 – 14.30 Surprise session

14:30 – 15:00 Brief discussion + feedback from presenters, opponents, and audience.

How to give a dynamic scientific presentation

Copied from https://www.elsevier.com/connect/how-to-give-a-dynamic-scientific-presentation

By Marilynn Larkin.

Giving presentations is an important part of sharing your work and achieving recognition in the larger medical and scientific communities. The ability to do so effectively can contribute to career success.

However, instead of engaging audiences and conveying enthusiasm, many presentations fall flat. Pitfalls include overly complicated content, monotone delivery and focusing on what you want to say rather than what the audience is interested in hearing.

There are two major facets to a presentation: the content and how you present it. Let’s face it, no matter how great the content, no one will get it if they stop paying attention. Here are some pointers on how to create clear, concise content for scientific presentations – and how to deliver your message in a dynamic way.

Presentation pointers: content

- Know your audience. Gear your presentation to the knowledge level and needs of the audience members. Are they colleagues? Researchers in a related field? Consumers who want to understand the value of your work for the clinic (for example, stem cell research that could open up a new avenue to treat a neurological disease)?

- Tell audience members up front why they should care and what’s in it for them. What problem will your work help solve? Is it a diagnostic test strategy that reduces false positives? A new technology that will help them to do their own work faster, better and less expensively? Will it help them get a new job or bring new skills to their present job?

- Convey your excitement.Tell a brief anecdote or describe the “aha” moment that convinced you to get involved in your field of expertise. For example, Dr. Marius Stan, a physicist and chemist known to the wider world as the carwash owner on Breaking Bad, explained that mathematics has always been his passion, and the “explosion” of computer hardware and software early in his career drove his interest to computational science, which involves the use of mathematical models to solve scientific problems. Personalizing makes your work come alive and helps audience members relate to it on an emotional level.

- Tell your story.A presentation is yourstory. It needs a beginning, a middle and an end. For example, you could begin with the problem you set out to solve. What did you discover by serendipity? What gap did you think your work could fill? For the middle, you could describe what you did, succinctly and logically, and ideally building to your most recent results. And the end could focus on where you are today and where you hope to go.

- Start with context. Cite research — by you and others — that brought you to this point. Where does your work fit within this context? What is unique about it? While presenting on organs-on-chips technology at a recent conference, Dr. Donald Ingber, Director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, described the pioneering work of others in the field, touched on its impact, then went on to show his unique contributions to the field. He did not present his work out of context, as though his group were the only one achieving results.

- Frame the problem: “We couldn’t understand why our experiment wasn’t working so we investigated further”; “We saw an opportunity to cut costs and speed things up.”

- Provide highlights of what you did, tied to the audience’s expertise and/or reasons for attending your presentation. Present the highlights in a logical order. Avoid going into excruciating detail. If people are interested in steps you don’t cover, they’ll ask and you can expand during the Q&A period. A meeting I covered on educational gaming gave presenters just 10 minutes each to talk about their work. Most used three to five slides, making sure to include a website address for more information on each slide. Because these speakers were well prepared, they were able to identify and communicate their key points in the short timeframe. They also made sure attendees who wanted more information would be able to find it easily on their websites. So don’t get bogged down in details — the what is often more important than the how.

- Conclude by summing up key points and acknowledging collaborators and mentors. Give a peek into your next steps, especially if you’re interested in recruiting partners. Include your contact details and Twitter handle.

- Keep it simple. Every field has its jargon and acronyms, and science and medicine are no exceptions. However, you don’t want audience members to get stuck on a particular term and lose the thread of your talk. Even your fellow scientists will appreciate brief definitions and explanations of terminology and processes, especially if you’re working in a field like microfluidics, which includes collaborators in diverse disciplines, such as engineering, biomedical research and computational biology.

- I’ve interviewed Nobel laureates who know how to have a conversation about their work that most anyone can understand – even if it involves complex areas such as brain chemistry or genomics. That’s because they’ve distilled their work to its essence, and can then talk about it at the most basic level as well as the most complicated. Regardless of the level of your talk, the goal should be to communicate, not obfuscate.

The first Bioinformatics and Biomedical Computing session day was held online on September 15 2021. The main theme was: ‘How to deliver your message in front of an heterogeneous audience’. The day started with four 15 minutes talks by senior staff members: Plagiarism (Antoine van Kampen), Data management (Silvia Olabarriaga), Internship projects (Perry Moerland) and Teaching for BSc/MSc/PhD students (Aldo Jongejan). In the second part the six PhD students in our section gave a 10-minute presentation (+ 5 minutes discussion) about a small part of their research and acted as chair and opponent during one presentation of a colleague. The third and final part was a surprise session. The same presentations were given in the same order however the roles were changed. The opponents from part two now had to present the work of the presenters they chaired in part two.